Whether you’re tackling a seminar paper, a bachelor’s thesis, or a master’s thesis: the task can feel overwhelming at first. But don’t worry – writing is a journey you can break down into four manageable phases:

- Brainstorming and planning

- Developing a structure and drafting the text

- Revision

- Formal editing and submission

By following a structured approach, you can avoid feeling overwhelmed right from the start. Here on this page, we’ll walk you through each phase of the writing process, offering practical tips and exercises at every step.

Tip: Discover detailed guidelines for bachelor’s theses in the Study Service Center’s Bachelor’s Guide. Remember, citation methods and directives differ between departments. Verify specific requirements and rules by consulting your department’s website and discussing them with your supervisor.

Phase 1: Brainstorming and planning

Launch into the exciting first phase by discovering and refining your topic. Start with some initial research and get a clear understanding of the formal requirements for your thesis. Remember, each department has its own specific guidelines for formal aspects, so be sure to check your department’s website!

Finding your topic

It all starts with an idea. But what do you do when inspiration is hard to find?

Our tip for finding a topic: Make it personal! Choosing a topic you’re passionate about can transform your thesis from a chore into an exciting journey. Since you’ll be working on it for a while, why not dive into something that truly interests you? Get creative and think outside the box! For example, if you’re studying business law and love bouldering, why not explore the legal aspects of liability in bouldering? Or investigate the insurance policies specific to bouldering parks and climbing gyms. The possibilities are endless when you connect your academic work with your personal passions! Can’t choose your topic? You have options here too: Narrow down your topic area to an aspect that excites you personally or link it to your interests.

Exercise: Finding a topic (based on Peterson 2013)

Use the following guiding questions to spark your creativity and help you discover your perfect topic. Take your time, go through each question, and jot down your thoughts and ideas as they come to you:

- What excites me? What sparks my curiosity?

- Which topics have recently inspired me?

- What surprises or astonishes me?

- What do I want to delve deeper into?

- What topics do I enjoy discussing?

- What recent changes have captured my attention?

- Which seemingly unrelated things might influence each other? How?

Narrowing down your topic

Once you have a rough idea, it’s time to narrow down your topic. The goal is to formulate a focused research question that will serve as the backbone of your thesis.

Narrowing down your topic is a crucial – arguably the most important – step in thesis writing. Take your time with this process.

Note: Ensure your topic isn’t too broad! For a bachelor’s thesis (according to the current curriculum), you’ll typically earn 10 ECTS credits, equivalent to about 250 working hours (or 31 full-time days). Select a topic that you can realistically explore within this timeframe. Often, focusing on one specific aspect of a broader topic is sufficient. Refer to the Study Service Center’s Bachelor’s Guide for more guidance.

Exercise: Criteria for narrowing down your topic (based on Grieshammer et al. 2022)

The criteria outlined below can help you generate ideas for narrowing down your topic. For each criterion, consider how you can refine your topic accordingly and jot down your thoughts in the column on the right. This exercise will help you determine which option(s) are most suitable for narrowing down your topic area.

To illustrate the practical application of these criteria, the table below includes specific examples for the topic “Burnout as a consequence of capitalism” (based on Grieshammer et al., 2022, p.176f).

Exercise: 3 steps to your research question (based on Grieshammer et al. 2022)

To shape your research interest into a precise research question, you just need to answer the following questions:

- What am I writing about? (identify the topic)

“I am investigating/working on/writing about…”

e.g: “I am investigating medium-sized companies in Austria…” - What do I want to know? (articulate the question)

“… because I want to understand/find out/understand…”

e.g.: “… because I want to understand how the measures for optimizing personnel management are designed” - Why do I want to know this? (define the objective)

“… to consider/determine/examine…”

e.g.: “… to examine whether these measures correspond to the principles of a modern corporate culture.”

Now, shape your answer to question 2 into a question, and you’ve got a first version of your research question.

For example: “Do the measures for optimizing HR management in medium-sized Austrian companies align with the principles of modern corporate culture?”

Then reformulate the answer to question 3 into a statement that begins with the following sentence: “The aim of this paper is to…”

For example: “The aim of this paper is to determine whether the measures for optimizing personnel management in medium-sized Austrian companies correspond to the principles of modern corporate culture.”

Now, you can derive a working hypothesis from your aim. Start it with: “I assume that…”

For example: “I assume that the measures for optimizing HR management in medium-sized Austrian companies do not correspond to the principles of modern corporate culture in most cases.”

Your first literature search

Now you can begin your research! This initial phase will give you an overview of your thesis topic. Is there existing research in this field? Can you identify key works and authors?

Our chapters on finding literature on a specific topic will guide you through this initial stage. If you have any questions, the WU Library offers a range of support services: Visit the Library Information or stop by the search_bar on Tuesdays. You can also schedule an appointment for a research consultation. We are happy to help!

Collect and reflect

Throughout the writing process, gather all your thoughts and ideas about your work. This practice ensures that you won’t forget anything important, and allows you to continuously reflect on your approach. Keeping a research diary can be especially helpful for this.

Exercise: Research diary

All you need for this exercise is something to write in, such as a notebook or a file on your phone or computer. From now on, this is the place for your thoughts and ideas surrounding the topic of your paper. Write down everything that is even remotely related to it – interesting sources, statements you have heard, questions and flashes of inspiration, … This way you can collect your thoughts and sift through and organize them later.

Phase 2: Developing a structure and drafting the text

The second phase of the writing process starts with creating a structure for your paper and concludes when you have written a rough draft. Begin by drafting a preliminary table of contents and gathering information for each chapter. Then, use this structure and collected information to write the first draft of your thesis.

The common thread: A preliminary table of contents

Before you start writing, it’s helpful to consider the structure that will best address your research question. What content needs to be included? What sub-questions should you explore?

Imagine you are giving a lecture as an expert on your topic: What points and aspects are essential for providing a meaningful, informative answer? These will form your chapters and subchapters (based on Wolfsberger 2016). Remember, your table of contents should be directly tied to your research question: Each section should relate to the research question, and every part of the table of contents must relate back to it.

Based on these considerations, you can create a preliminary table of contents for your paper. This serves as a framework to guide your work. If it later turns out that a different structure makes more sense, you can adjust it accordingly.

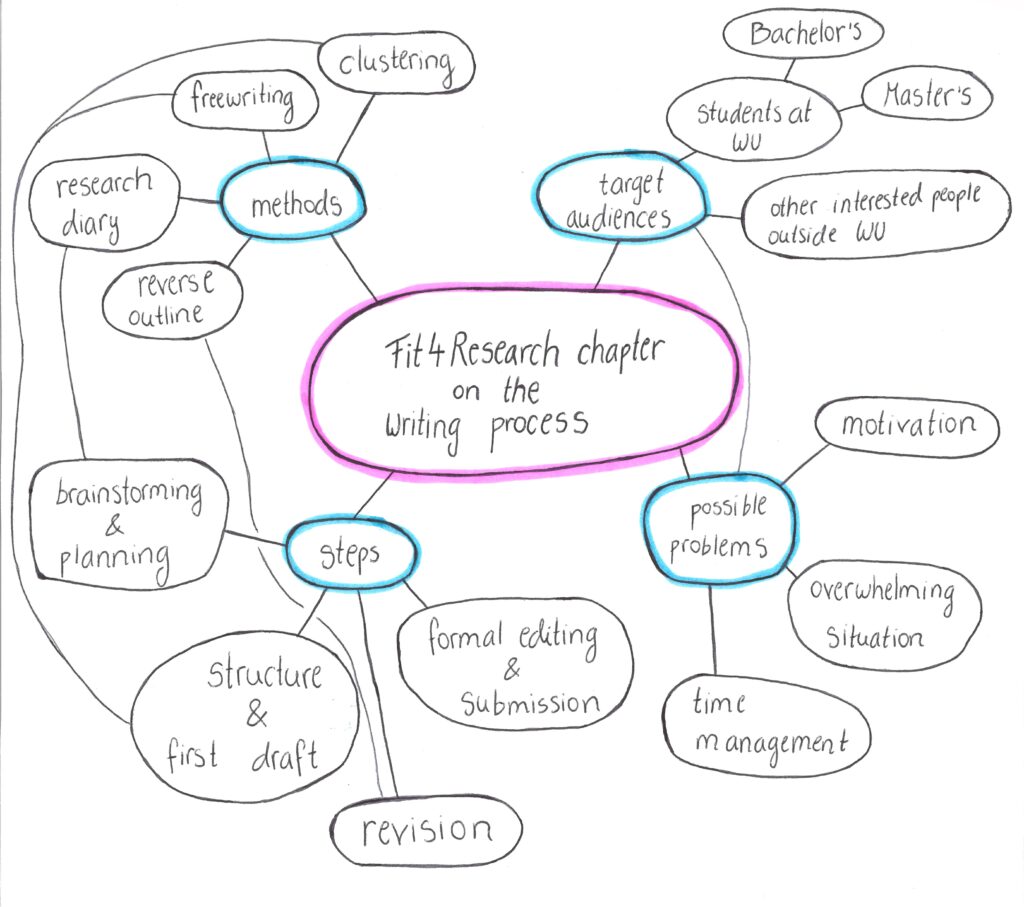

Exercise: Clustering (based on Wolfsberger 2021)

Clustering is a powerful brainstorming technique for developing concepts for your text, like the table of contents for your paper. It helps you quickly get your ideas down on paper, activate and structure your knowledge, and ease the transition from reading to writing.

This is how clustering works:

- Begin by writing a core concept in the center of a blank sheet of paper and encircle it.

- Next, jot down every idea that comes to mind related to the core concept. Encircle each aspect and connect them with lines to the core concept or to other circles. Don’t overthink it; place terms where they spontaneously make sense to you. This will gradually form a network with an intuitive order.

- Once complete, “evaluate” your cluster: Consider which parts are most important and which aspects can be omitted.

- Optionally, create a second cluster focusing only on the content you want to emphasize in your writing. Here, develop a logical order for your text modules or paragraphs.

Use your completed cluster as a writing plan. Progress from circle to circle and from aspect to aspect, concentrating on each aspect as you formulate your ideas.

Freewriting is another tool that can help you to collect and organize your thoughts on the structure of your work. If you would like to try freewriting, the University of Vienna has a very helpful guide [German only].

Accumulating knowledge

Now that you have your chapter structure in place, you can begin accumulating knowledge. The type of knowledge you gather can vary widely depending on your topic: it might involve literature such as books and journal articles, or data such as interviews, financial information, and statistics. You will learn how to access this information in the chapters on research (How to find…) and using search tools (WU catalog, Google Scholar & Co.).

When selecting your sources, ensure they meet academic quality standards. A quick and effective method to evaluate them is the CRAAP test.

Next, systematically read your chosen sources (using methods like SQ3R), extract relevant information, interpret findings, and summarize key points.

Exercise: Flash proposal (based on Grieshammer et al. 2022)

As you gather and select literature, it’s helpful to keep in mind what additional literature you need and how the literature you have found so far supports your research.

A proposal, also known as a concept, outline or research proposal, helps you define the framework of your work and identify the materials necessary to answer your research question.

With a flash proposal, you can create a draft of your proposal in no time at all. To create a flash proposal quickly, follow these steps: Answer the key questions below in freewriting style as swiftly as possible. Don’t know what to write? Jot down the question you need to answer first to progress through the key questions.

Topic:

- What is my paper about? What is the central idea?

Research question/hypothesis:

- What do I want to find out, show, or test? Which aspects are interesting?

Goals, personal aims of the research:

- What should the result of the work be? Why is it significant?

Methodological approach:

- How will I proceed? Which methods specific to my field will I employ and why?

Material:

- What will be studied? Which empirical data, primary texts, sources or phenomena will I study?

- What criteria will guide my selection, and how broad or narrow will my focus be?

- What key scholarly works will I reference?

Resources:

- Which methods, literature, workshops, or advisory services will support my research?

Identifying the problem and its relationship to existing literature or research:

- What state of research am I connecting to? What is the research gap, the problem?

Setting a timetable: What milestones will I set to guide my progress? When do I aim to complete the project?

Note: The questions outlined above serve as a foundational framework for your proposal. However, the specific content and format required for your proposal or concept will primarily depend on your supervisor and the guidelines of your institute or department.

Tip: Reference management software like Zotero, Citavi, or EndNote can greatly assist you in organizing your collected sources. In our chapter on reference management, you’ll discover details about WU citation styles and guides on using reference management software effectively. The WU Library also offers workshops where you can learn how to navigate different reference management software options.

Writing a draft

Now it’s time to dive in: Your paper has a structure in the form of a table of contents, and you’ve thoroughly reviewed all the materials needed to address your research question. You’re now prepared to write the initial draft of your paper!

Note: Remember, this is just the first version of your text! You don’t need to craft a flawless paper right from the start. The goal is to capture all the relevant aspects of your work and produce content. Your citations don’t need to be perfectly formatted at this stage; just make sure to be consistent about writing down your respective sources in some form—otherwise you risk forgetting where you got your information from. Revision and polishing will come in the next phase of your writing process.

Phase 3: Revision

In the third phase of the writing process, you’ll revise your draft text, concentrating solely on content and clarity of expression. Spelling, grammar, punctuation, and citations will be addressed in the next phase. This stage is where your text starts to take shape and refine itself, it becomes “good”—this process can take time, so ensure you allocate enough for thorough revision.

Tip: Get as much feedback as possible! Share your work with different people and ask for their insights. This can provide fresh perspectives and help you refine your paper. Clearly communicate the type of feedback you’re seeking: Are you interested in the clarity of your arguments? Or do you need input on the overall comprehensibility of your work? Perhaps you’re looking for feedback on your writing style?

The text is analyzed and improved on two levels:

Structure and line of argument

When revising the text structure and line of argumentation, concentrate on elements such as focus, structure, perspective, relevance, and logical flow. The following guiding questions can help you in this process:

- Will the readers be able to understand the text?

- Can readers easily follow the structure?

- What effect does my text have? How is it perceived?

- Have I provided enough information?

- Am I following a predefined structure?

- Have I addressed my target audience effectively?

Exercise: Reverse outline (based on Scheuermann 2022)

This exercise can help you improve the structure of a text section retrospectively. Follow these steps:

- Read: Take your time to read through the section you want to work on.

- Highlight: Identify and mark the individual trains of thought. Typically, each train of thought will be outlined in a separate section. Add content or remove repetitions as needed.

- Headings: Write a provisional heading for each train of thought that captures the key message of the section. Use these headings to check whether the order of thoughts makes sense in the overall context.

- Rearrange: If necessary, rearrange the sections and their corresponding headings into a more logical sequence.

- Review: Read through the text again. Add any missing transitions between sections. Ensure each section clearly conveys the content indicated by its heading.

- Finalize: If everything is coherent, remove the provisional headings or develop them into “real” headings that remain in the text. And that’s it!

Tip: Ask ChatGPT to create a reverse outline for you. It might provide fresh ideas for structuring your text.

Sentence and word level

Once you have finished revising your text structure and outline, you can take a closer look at your text at the sentence and word level. Important aspects here are accuracy of language, redundancy, sentence structure, sppropriate transitions between sentences and ideas, etc.

These key questions can guide your revision:

- Does this reflect my voice? Or does the text feel overly formal or awkward? (Being scientific doesn’t mean being incomprehensible!)

- Is every word necessary?

- Are technical terms used clearly, unambiguously and consistently?

- Can I find words that fit better?

- Do the sentences have an appropriate length?

Tip: Read your text out loud. This helps you evaluate its flow and identify any inconsistencies.

Phase 4: Formal editing and submission

Almost there! In the final phase of the writing process, you refine your work before submission. Pay attention to the following:

- Spelling and grammar

- Punctuation (e.g. commas)

- Layout

- References, citations, and adherence to citation rules

At this stage, it’s crucial to seek feedback from your peers one last time. After that, your work will be ready for submission and grading. Well done!

Resources

Books on academic writing that are available in the WU library

AI tools (list from the Virtual Competence Center VK:KIWA – in German only)

Reference management software (download links and instructions)

All information on citing correctly

Useful books:

- Peterson, B. (2013). Die 99 besten Schreibtipps: Für die vorwissenschaftliche Arbeit, Matura und das Studium (2nd. ed.). Krenn.

- Wolfsberger, J. (2021). Frei geschrieben: Mut, Freiheit & Strategie für wissenschaftliche Abschlussarbeiten (5th ed., revised). UTB.

References

Grieshammer, E., Liebetanz, F., Peters, N., & Zegenhagen, J. (2022). Zukunftsmodell Schreibberatung: Eine Anleitung zur Begleitung von Schreibenden im Studium (5th ed.). Schneider Verlag Hohengehren GmbH.

Peterson, B. (2013). Die 99 besten Schreibtipps: Für die vorwissenschaftliche Arbeit, Matura und das Studium (2nd ed.). Krenn.

Scheuermann, U. (2022). Die Schreibfitness-Mappe: 60 Checklisten, Beispiele und Übungen für alle, die beruflich schreiben (3rd ed.). Linde international.

Wolfsberger, J. (2021). Frei geschrieben: Mut, Freiheit & Strategie für wissenschaftliche Abschlussarbeiten (5th ed., revised). UTB.